The latest installment of the College of Education National Deaf Center for Postsecondary Outcomes’ innovative game for deaf youth, Deafverse, will be released this month and aims to address college readiness through the lens of a fantastical new world. Deafverse is a first of its kind free online adventure game created by a deaf team at the National Deaf Center to serve deaf youth by building critical self-advocacy, college and career readiness skills. The game utilizes American Sign Language (ASL), English text and audio voiceovers and is available on both desktop and mobile. The newest version, Legends of the Eldertree, is the third chapter in Deafverse, which was originally released in September 2019 and has since grown to nearly 20,000 users and over 500 virtual classrooms nationwide.

“Game-based learning can drive real growth—especially when it’s designed with the right audience in mind,” said Carrie Lou Bloom, director of the National Deaf Center for Postsecondary Outcomes. “But for deaf youth, there was a major gap: no online educational games that were accessible in ASL, culturally relevant or grounded in the realities of deaf experiences. Deafverse was created to fill that gap.”

Data from the National Deaf Center shows there are an estimated 265,774 deaf youths between the ages of 14-22 living in the United States, many of whom are the only deaf person in their school or community, especially in rural settings. For many, this means reduced access to career-connected learning that typically happens in social networks, creating a need for specialized interventions.

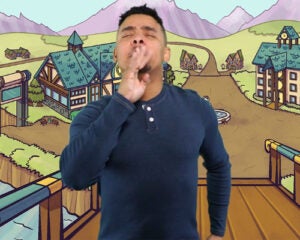

The choose your own adventure educational online game was designed for deaf and hard-of-hearing teenagers, educators and parents and is set in a fantasy world. It is meant to address gaps in services for deaf youth, strengthen self-advocacy and self-determination skills, support college and career readiness and connect deaf youth with role models.

Previously, the first installment of Deafverse, Duel of the Bots, helped student users to build self-advocacy skills while rescuing a town from a glitching robot. Meanwhile, the second chapter of the game took players on a journey of career exploration while fending off a rampaging kraken.

In this new installment, players discover that elves have disappeared without a trace, leaving behind ruins and a massive, magical tree. As new students at Eldertree College, players will discover important clues to the elves’ mystery.

“This project came to life through the work of an incredibly talented, deaf-led team of developers, artists, writers, actors and educators,” Bloom said. “We weren’t just building a game—we were building something we all wished we had growing up. It’s a tool rooted in research, lived experience and community—and it’s meant to open new possibilities for the next generation.”

According to the National Deaf Center’s data, an estimated 5% of deaf people are enrolled in postsecondary education, compared to nearly double that percentage for hearing people, and only 22% of deaf people have completed a bachelor’s degree or higher, which is nearly 16% less than the attainment rate of their hearing peers.

Legends of the Eldertree aims to help users learn how to navigate a typical college application process, gain a better understanding of common college financing options and become familiar with resources available on higher education campuses. Additionally, players will explore options for building connections with others around campus, navigate barriers to equitable access and select preferrable accommodations for different situations that they could experience throughout college.

Additionally, the game will include new features such as maps that players can click on to explore the world, an in-game tablet that users can carry virtually and a new fantasy world with elves and dungeons.

“Deafverse has become more than a game—it’s a conversation starter, a classroom resource and a community-builder,” Bloom said. “It’s gone far beyond what we imagined. We’ve seen incredible creativity and leadership emerge through this project. People across the country are using Deafverse in ways we never anticipated, from summer camps to transition planning.”

Deaf youth who have played Deafverse reported an increased level of confidence in their ability to make decisions and advocate for themselves, according to data from the National Deaf Center. Since its inception in 2019, the game has grown to 18,109 users who have obtained a combined 30,190 badges.

Bloom said that it is incredibly validating to hear about the difference Deafverse makes in students’ lives because this work is personal. She said that like many deaf people, she endured unskilled and unprofessional interpreters, having to rely on them for access to information which often left her stuck navigating different dynamics in real-time.

“When I learn that it helped someone feel more prepared for college or more confident in asking for accommodations, it reminds me why we started this in the first place,” Bloom said. “So many deaf youths grow up without access to content made with them in mind. To be able to fill that gap—and do it in a way that’s fun, culturally rich and grounded in community—is something I’m deeply proud of.”

Educators are increasingly turning to the game as a resource since Deafverse Classroom became available in 2023. More than 1,400 student accounts have been created by their teachers and there are 568 virtual classrooms to date.

“The feedback has been both humbling and motivating,” Bloom said. “Teachers tell us their students light up when they play Deafverse—it’s often the first time they’ve seen themselves reflected in a game. Some students tell us it helped them build confidence, ask for interpreters or speak up about their needs. Others just say it made them feel less alone.”

Now, Bloom said her hope is that Deafverse becomes part of a bigger movement—one where deaf people don’t have to fight so hard to access the same opportunities.

“I want Deafverse to continue growing, with more stories, more content areas, more ways to explore who you are and what’s out there,” Bloom said. “I also hope it continues to spark ideas in other fields—about how accessibility and cultural relevance can drive better design, not just for deaf people, but for everyone.”